On the first of September (called T-day), the long-awaited two-pot retirement system came into effect (it was announced and promulgated on 1/3/2021), and it is still difficult for the man on the street to decipher exactly how this will affect them.

There are some good visuals, videos, and calculators available to walk you through the process step by step, so instead of reinventing the wheel, I will give you links to them. However, I have tried to simplify the process so you can make informed decisions.

Before going any further (and those of you that might get bored halfway through), if you were over the age of 55 on 1 March 2021, you would have opted out of joining the two-pot system but can opt in at any time until 1 September 2025. Your pension provider should already have had that conversation with you. (Should you opt in? Short answer – yes, but speak to your financial advisor/planner tout-suite to get individualised advice).

Why the pension system was changed

There is no easy way to say this, but the main reason this new law was put in place is to protect workers ‘from themselves’ and stop them from cashing out their pensions when leaving one employer to join another – which is happening much more frequently than ever before (the average tenure in a job for workers in their 20s is less than two years – rising steadily to around seven years for those in their 50s).

It’s just a fact of life today that if you want to significantly boost your earnings above the normal inflationary rise, you’re probably going to have to move jobs. Companies are still behind the curve in identifying and promoting valuable workers, and they often wake up and try to counter-offer when someone valuable hands in their resignation. (My tip – never accept it; you’ll just end up in the same position a year or two down the line.)

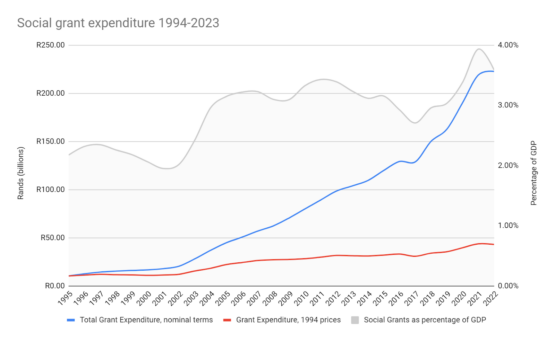

The second reason this change has been activated is due to the fact that 60% of workers who reach retirement age are significantly underfunded for their retirement – this puts a load on the state with old age grants in an era where grants, in one way, shape or form, are already a massive portion of RSA’s annual budget. There has been an excellent article written on this here, and here is a graph from that article:

This chart shows state expenditure on social grants since 1994. Source: GroundUp with data sourced from National Treasury, StatsSA, and UCT’s Centre for Social Science Research.

There has been an almost 400% increase (as a percentage of GDP) in grants since 1994.

A third reason this was put in place was to give workers access to the funds without resigning. (This had become a significant issue in the government sector, and labour resistance is part of the reason this system was delayed and watered-down – apart from the logistical nightmare it has caused pension fund companies.)

Opting out: Over age 55

Hopefully, your pension provider will have communicated the option of opting in or out of the new two-pot system, and you’ll have been able to make an informed choice.

In a nutshell: If you were over 55 on 1 April 2021, were a member of a pension or provident fund and are still a member of that fund, you were automatically opted out of the two-pot scheme. In other words, you can opt to keep the status quo and be able to take the full amount as a cash lump sum as per the ‘old’ rules if you resign from the company (pre-retirement lump sum rules, as shown below, would apply).

You could also retire from the fund you have been contributing to upon leaving your current employer or retiring (this is an event, not a date) – and all the old rules will apply. Future contributions will still go into the old fund just like they used to. You will not have a savings pot that you can withdraw from though.

You will have the opportunity to opt in, but ONLY for one year, until 1 September 2025. If you haven’t had this discussion with your financial advisor, please do so as soon as possible.

Everyone who was employed in the same company and a member of the same retirement fund before and after 1 September 2024 will have an ‘old’ vested portion – with old rules – and a new two-pot system with the embedded savings pot.

Before you decide to keep the ability to cash in your “vested” pension on your resignation and take the Sars punch on the jaw, please have your financial advisor do the math for you. There is no investment out there (yes, even offshore) that is going to make up that 37% hole you put in your investment in your lifetime.

Vesting rights

If you have been automatically opted into the two-pot system – under the age of 55 on 1 April 2021, or you are over age 55 and have chosen to opt in, you are now a proud member of the two-pot system, and while this is called the two-pot system, for anyone who was employed at the same company before and after 1 September 2024 there are going to be three pots:

Vested, savings and compulsory.

Ten percent of that vested portion, to a maximum of R30 000, will go into your savings portion of the “after two-pot” savings section as ‘seeding money’. This is what it is going to look like on 1 September 2024 – let’s use R1 million just as an example:

- Vested: R1 million minus R30 000 seed money = R970 000.

- Savings pot: R30 000 (seed money).

- Compulsory: R0 (waiting for the end of September’s contribution).

From here on out, the vested portion will grow in line with your investment choice (this would be whatever you chose prior to implementation or if you have elected another option), and the savings and compulsory portions will grow by the monthly contribution plus the fund’s growth (again invested in your elected (or prescribed if you have no choice) investment choice).

The vested pot (R970 000 portion)

Your vested portion, i.e. before 1 September 2024, will be treated in the ‘old’ way when you resign from a company:

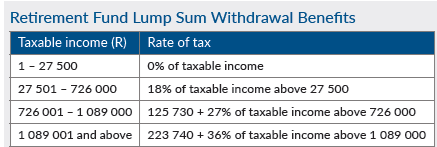

1. It can be cashed in, and lump-sum tax rules will apply. This is the table from the 2025 Sars handbook (you can contact me if you don’t have a copy of it). Note that this allowance and scale is a lifetime amount and accumulated by Sars. If you take a retrenchment/severance benefit and these rules have been applied, then you may be in a higher bracket than you realise.

2. There will still be a R27 500 lifetime pre-retirement tax-free portion on the vested capital. Please also note that if you take these lump sums in pre-retirement, despite paying tax on them, they will be deducted from your R550 000 retirement tax-free sum, which usually should only be taken upon retirement.

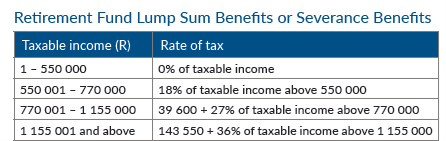

3. On retirement from age 55, the normal lump sum rules at retirement apply; in other words, you can still take up to one third of the fund as a cash lump sum (but the rate at which you are taxed on it is going to depend on how much you cashed out pre-retirement. At retirement, the tax is different from pre-retirement – as shown below:

After 1 September 2024: The two-pot system

Managing this transition to the two-pot system is going to be messy. Pension providers are already scrambling to cope with the change, and now there is going to be an avalanche of requests to dip into the savings portion. Hint: Don’t expect a quick response. In addition to the tax, you’re likely to be charged fees, too (averaging around R500 per withdrawal – so please ask first). Here are a couple of calculators to help you from Discovery and Momentum.

The savings pot (R30 000 portion and one third of future contributions)

Let me just clear up one frequently asked question – how are these funds going to be invested, and can we choose for the three pots to be invested differently?

The split of the invested funds into the three pots is essentially a book-keeping exercise that the providers will undertake (one of the reasons they will be demanding a relatively stiff fee per withdrawal), but practically, these are all going to be invested the same way – as dictated by your pension fund rules (or your choice of funds if that is available).

When you make a request to access a portion of the savings, which you can do once a year (minimum R2 000), then the fund managers are going to sell assets (unit trusts for example) in order to make that ‘liquidity’ available to you and your administrator is going to make the relevant book-keeping changes. One small ray of sunshine – capital gains tax is not levied on funds invested in formal retirement funds, and you are not taxed on the interest portion either.

One of the major changes that you’re going to have to get used to is how these withdrawals are going to be taxed. Unlike the “before two-pot” regime (and your vested portion), where the lump sum withdrawal rules are applied, any income withdrawn is going to be taxed at your marginal rate. In other words, it will be added to your income and taxed at that rate. (You can get that table from the Sars pocket summary issued at the time of the budget – you’re welcome to ask me for it.) Put simply, if you’re earning more than R56 000 per month gross, you’ll be taxed at 39% or more. That’s a huge hole to put in your savings!

For every new contribution you or your employer make to your pension:

- One third will be ‘allocated’ to the savings portion; and

- The other two thirds will go into the compulsory portion.

The compulsory portion (two thirds of future contributions)

This, in essence, becomes your long-term pension savings. If your savings component is not taken before retirement, it, too, will be added to your overall pension, matching what it would have been if the two-pot system had never been implemented.

When you resign from a company, you will have the option of cleaning out your savings portion and taking the marginal income tax hit or ‘preserving’ the entire pension (without paying tax) until you are ready to retire from it (with much less onerous tax consequences). The compulsory portion will have to be preserved in one shape or form – in your individual capacity or by transferring it to the new employer.

Remember that from age 55, you can ‘retire from’ the fund, one third of the savings portion can be cashed out, and the first R550 000 (lifetime allowance) is tax-free. The rest must be used to purchase a compulsory annuity – from this, you will draw an income, and the marginal income tax tables would apply as normal (unless it is below R165 000). Many of my clients, on reaching retirement, choose to take the up to R550 000 tax-free portion (or what is left of it) and use the rest as an annuity (aka ‘pension’). You don’t really want to take that pension or annuity if you’re still earning – because it’s going to be added to your active income and taxed at that marginal rate (up to 45%).

Cautionary note

While it might be tempting to access the savings portion of your pension pot to the max, I would caution against it, especially before talking to your financial advisor.

Your pension contributions are deducted from your income before tax, effectively lowering your tax bill. Inevitably, when Sars gives with one hand, it always gets it back with the other somewhere down the line. So, remember that when you access your savings pot pre-retirement, Sars is the only winner, even more so now that it uses the higher ‘marginal tax rates’. Consider this carefully.

Your pension provider is going to get a tax directive, and the tax will be withheld from the savings payout and the income added to your taxable income – which could push you into a higher bracket or out of the threshold of no tax into the 18% bracket. Over or under-recovery by Sars will be done at the end of the tax year in your final assessment. (Hint: Thinking outside of the box, you can bring this down with contributions to a personal retirement annuity, for example, in the same tax year if you recoup the funds during the tax year and you’re below the 27.5% or R350 000 annual maximum for contributions).

If you owe Sars, then it will help itself to those funds (called IT88), especially with low-hanging fruit like withholding tax on a pension withdrawal or retirement. Unless you didn’t already know, Sars can go into any of your bank accounts and help itself to funds owed (if you’re not in the objection or appeals process). It is increasingly foolhardy not to be on top of your tax; all your IRP5s from your savings and investments are automatically lodged with Sars, and it knows what properties you own.

When you change employers, you can still do what is called a ‘Section 14 transfer’ of your pension fund – in other words preserving the three components (vested, savings and compulsory) without triggering tax. These three pots have to be kept separately in the new ‘preserver’ or by your new employer – this is a bookkeeping exercise, and the funds are not going to be physically divided.

When deciding whether to move your pension to a new employer or preserve it ‘privately’, consider that you may at some point go into semi-retirement. This may require you to draw an income from your pension assets to supplement your income. If you have privately preserved your pension from previous employers, you can draw an income from this portion (after a compulsory annuity is purchased) and still make contributions as an active member of your current employer. If you have transferred all of your assets to your new employer, this becomes much more difficult. Again, seeking financial advice is crucial in these matters.

On a positive note, remember that funds invested in formal pensions and compulsory annuities are not estate-dutiable (except for unrecouped contributions), and in terms of the Pension Funds Act, you are not obliged EVER to retire from the investment. (You used to have to retire from it by age 70.) Your advisor should be considering this when drawing up your financial and estate plan.

Here is a good Moneyweb article that will give you more insight into this new regime.

If you want to be cynical about this – consider that Sars is anticipating a R5 billion windfall tax from withdrawals from this newly formed savings component. That’ll pay for grants for 45 days.

P.S Emergency savings

The harsh reality is that most South African workers do not have an emergency fund, and the sum total of all their savings and investments is in their retirement fund – which is why Sars is anticipating such a huge windfall when members access their savings pot.

The high interest rates and inflation have been impacting disposable income for those workers, so this withdrawal will come as a welcome relief to many, especially if they earn below the threshold of R95 750 pa (under about R8 000 pm). If you’re closer to the 39%+ marginal rate, this withdrawal is going to be an expensive loan on your future.

An easy-to-access emergency fund should be one of the very first investments/savings you put in place in your working life. Most banks make it very easy for you to do that with savings pockets at decent rates. In my opinion, when you’ve got it to about three months of after-tax income, then you can start thinking about other investments.

In summary, these changes can have a huge impact on your retirement funding – please discuss this with your financial advisor/planner, especially if you’re over the age of 55 or considering withdrawing from the savings pot.

COMMENTS 0

You must be signed in to comment.

SIGN IN SUBSCRIBE

or create a free account.

Free users can leave 4 comments per month.

Subscribers can leave unlimited comments via our website and app.