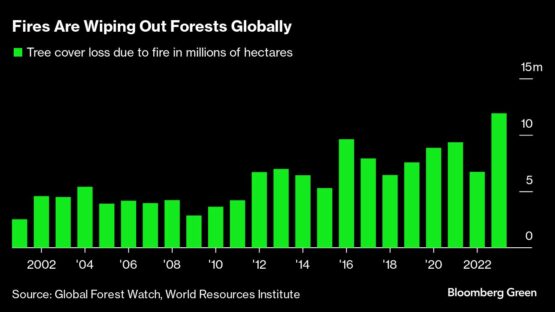

After the world posted its worst year for wildfires, with an area roughly the size of Nicaragua scorched in 2023, one plane model has become the most important aircraft on Earth.

A specialised amphibious firefighting plane — commonly called a Canadair after its original manufacturer — is unique in the market for its size and manoeuvrability. It can hold as much as 1 621 US gallons (6 137 litres) of water — about 20 bathtubs full — and travel at more than 200 miles per hour (322 kilometres per hour). In a quick swoop, the planes scoop up water from lakes or seas — filling up in 12 seconds — and fly as low as 100 feet (30 meters) above burning infernos to douse flames.

As climate change makes wildfires more frequent and intense around the world, these acrobatic water-bombers are needed now more than they’ve ever been before. Yet they were out of production for almost 10 years. This has now changed.

De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd., which acquired the rights to the aircraft in 2016, reached new agreements with European Union countries this year to provide 22 DHC-515 firefighter planes, the brand successor of the Canadair. The order will be the first time De Havilland makes these €50 million ($55 million) planes. While production won’t finish until the end of 2026 at the earliest, the EU is willing to wait for a firefighting plane considered incomparable to anything else available.

“The so-called Canadair is the only functioning, operational aircraft in that category in this moment of time,” Hans Das, deputy-director general for European civil protection and humanitarian aid operations at the European Commission, said in an interview. “Over the last few years, we have seen forest fires expanding into all of Europe. Nobody escapes anymore.”

Wildfires have been raging across the continent this year — most ferociously in Greece and Turkey — as the world recorded its hottest summer ever. Across the Atlantic, Brazil’s Amazon rainforest has been on fire, wafting toxic smoke into the country’s largest city Sao Paulo in recent weeks. In North America California battled one of its worst wildfires on record in July and blazes have raged across De Havilland’s home province of Alberta. Fires were still smoldering under the snow in Canada in March after unprecedented wildfires in 2023.

Most firefighters are on the ground during a wildfire, but planes play an important role in helping dowse fires with water or stopping the spread with retardant.

“As fires continue to increase both in number of fires and in the scale, there is just more and more need for aerial firefighting assets to help support those firefighters on the ground so they don’t get their butt kicked,” Paul Petersen, executive director of the United Aerial Firefighters Association, said in an interview.

A Canadair CL-415 amphibious firefighting aircraft at the Hellenic Air Force’s 113 Combat Wing air base in Thessaloniki, Greece, in June 2022. Image: Konstantinos Tsakalidis/Bloomberg

Petersen estimates the world needs twice the amount of firefighting aircraft currently available to meet demand.

Riva Duncan, a retired fire chief with the US Forest Service, agreed that demand has been exceeding aircraft availability. “The growing number of fires we’re having, the lengthening of the fire season into a fire year, larger, more destructive fires — we need every tool in the toolbox to be able to manage these fires and aircraft’s a big part of that,” she said.

Quebec-based Bombardier Inc., the previous manufacturer of the Canadair planes, sold off the unit in 2016 as it dealt with a series of financial difficulties. From 2015 until the new EU order, the firefighter planes had been out of production.

De Havilland first discussed restarting production of the planes in 2019, but due to the high costs, it needed a firm commitment of a minimum number to get their suppliers on board for parts, according to Neil Sweeney, De Havilland vice president of corporate affairs. He said the EU’s order for 22 planes was enough to start things up again.

The aircraft will be delivered to Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Spain, Italy and France. Some planes are earmarked for rescEU, the bloc’s civil protection mechanism, while others are for individual countries. De Havilland estimates that it will take 18 to 36 months to build the new aircraft in its Calgary plant, but Sweeney said the process should become quicker with time.

The wing assembly line for the DHC-515 firefighter at the De Havilland Canada production facility in Calgary, Canada, in February. Image: James MacDonald/Bloomberg

The EU started looking at expanding its aerial firefighting fleet in 2020 — taking on board supply chain lessons learned during the Covid pandemic. With fires happening simultaneously across the continent, the bloc found sharing resources across countries does not work if there aren’t enough planes.

“When everybody is facing the same difficulty, then the system gets paralyzed,” Balazs Ujvari, a spokesperson for the European Commission, said in an interview. “If your house is burning then you cannot also help the neighbor’s house that is burning.”

For this fire season, the EU has access to 26 firefighting planes from nine member states.

De Havilland said there are approximately 160 Canadair planes in operation in 10 countries: Turkey, Morocco, Canada, the US, France, Croatia, Spain, Italy, Greece and Malaysia. There are other aircraft capable of water bombing, but they either hold less extinguishing agent or they’re good for one big drop before needing to return to a station for a slower refill. Canadairs, on the other hand, can circle back and skim an open body of water again and again, refilling almost at full speed.

While countries around the world have made regional deals to share aerial firefighting resources, including lending out aircraft during off-seasons for wildfires, climate change has been making this a logistical nightmare. Countries are dealing with longer fire seasons and places that previously didn’t have many fires are seeing them more regularly.

Firefighters work to control the East Attica wildfire northeast of Athens in August. Image: Nick Paleologos/Bloomberg

This is one reason De Havilland expects to see more demand for firefighting aircraft in the future. The other is that many countries will be keen to upgrade aircraft in their fleet — which may be up to 50 years old. Over time, planes that scoop salt water can suffer from corrosion, and in warmer climates they may begin to rust.

The new DHC-515 aircraft will have similar water capacity to its predecessor, but will have a few upgrades. These include improvements to the water drop control system, the avionics, the rudder control and the air conditioning.

Mike Flannigan, a research chair in emergency management and fire science at Thompson Rivers University, said De Havilland may have cornered a market for these types of planes now, but other manufacturers will likely sense an opportunity as wildfires become a more difficult problem for countries to tackle.

“I expect they might get some competition eventually if this market continues to grow,” he said.

Follow Moneyweb’s in-depth finance and business news on WhatsApp here.

COMMENTS 0

You must be signed in to comment.

SIGN IN SUBSCRIBE

or create a free account.

Free users can leave 4 comments per month.

Subscribers can leave unlimited comments via our website and app.